Democracies: now we are talking

Nowadays, one of the most common forms of government is Democracy. It is usually based on the idea of equality among the citizens of a country. Due to this, laws affect similarly to all of us and the political parties are elected in a fair way. At least, theoretically. Reality is quite different, as we all know. However, before talking about this matter, it is worth pointing out the origins of Democracy.

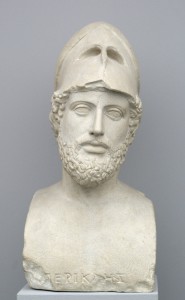

Officially, it was implanted firstly in Ancient Greece, in Athens, during the government of Pericles. Its main precedent was the legislative reform established by Cleisthenes in the last few years of VI century BC, which is called isonomia, i. e., “equality of political rights”. Before that, it should be noted the work of Solon, a lawmaker that in 594 BC made a big effort in order to solve several political, economical and moral problems of Athens. One century and a half later, Democracy began as an institutionalised political system.

Source: Wikimedia

Up to then, the Areopagus was the organism which ruled Athens; it consisted of a rich and powerful oligarchy of elder citizens, which controlled the magistrates (archontes). Corruption was widespread inside it, and as time went by more voices demanded the reduction of its functions and privileges. Democratic reform made it, and Areopagus turned into a minor organism. It was one of the main causes of the coming of Democracy, but there were several more, as, for instance the hoplitic system of warfare. All citizens that could buy the panoplia (defensive and offensive weapons), had to fight; many of them died or were hurt. Nevertheless, they could not take part in the government.

In this manner, each citizen of Athens had the same political rights. It was called demo + cracy, that is to say, the government of the demos, the people. However, this Democracy and ours are about as dissimilar as it could be. Grosso modo, one person was considered an Athenian citizen only if he was a free man born in Athens. It means that slaves, women and foreign people never had political rights. In fact, not all free men where citizens initially, but only those who had certain wealth. But owing to the wars that were developed during many decades, it was necessary to allow poor people to fight; for example, thetes, a low class, became an important section of the Athenian army, and as it happened, they demanded political rights. Democracy turned into what was called “radical Democracy”, but slaves, women and foreigners were still ignored.

Current society has a different approach to the concept of Democracy: equality of political rights, without exclusions of gender neither wealth aspects. During XX century democratic ideas have been established in many countries. It has confronted with other political systems, such as dictatorships, and it has been linked both to republican and monarchical regimes. Theoretically, all legal age citizens can decide who is going to be their president/prime minister.

Nevertheless, some incongruities exist. For example, in Spain we vote to a political party, mainly PSOE of PP, not the politicians. That is why a notable portion of the population demands open lists. Another relevant aspect is the kind of Democracy we have: a “representative” one, translated in reality in a government that takes the vast majority of the decisions. This is the most common model, but it is strongly criticized, especially during this crisis period. Some people propose a different version of democracy: some sort of participatory one, characterised by a greater participation of citizens in political matters, as for instance with more referendums (see the Swiss case).

Each model has its pros and cons. Political parties consist of people with quite different ideologies. Inside PP (the party in power right now), for example, tendencies vary from moderate to extreme right, including conservatives and liberals. And linked to the democratic system we usually see bipartidism and populism. Also, corruption is very common; every so often is discovered a new case, starred by politicians of different ideologies. But many of them are finally absolved because of their power and influence.

For all these reasons, an specific demand has became so popular: “Real Democracy Now!”. However, what is “Real Democracy”? Which are its main postulates? This is a difficult question, and surely there is not an unique answer. People who criticize the current system demand at least a more participatory model, which from my point of view is necessary. The extreme is what is often called “pure Democracy”, where people participate in assemblies. That would be a good way in small societies, but I consider it impossible in big ones.

Thus, do we live in Democracy? I guess we do, but it is in no way a perfect model and therefore it should be improved with more participation and transparency.

Diego Chapinal