Nothing New on the Southern Front: Why a Military Intervention in Libya Would Be Ineffective (For the Moment)

“Addressing the root causes of irregular and forced displacement in third countries”. This is the title of one of the paragraph in the European Agenda on Migration, recently presented by the EU Commission, the most relevant point of which is the quota system for EU migrant distribution. Leaving aside critiques – particularly, the relocation criteria and disagreement of United Kingdom, France, Germany, Spain, Poland, Hungary – as explained in another article, going beyond the “simple” rescuing of human lives is fundamental for avoiding tragedies; especially in the Mediterranean case, focusing efforts on Libya is an option which could drastically reduce the flow of irregular migrants.

The Guardian recently revealed a possible European military intervention on Libyan soil – then denied by the High Representative Mogherini -, having raised again the proposal for strong action. Together with the declaration of Abdul Basit Haroun, advisor of Tobruk government– according to whom Islamic State’s militants have reached Europe hiding themselves in the crowd of irregular migrants – it undoubtedly adds concerns and justify the need of military intervention.

Some believe that such an action would be the most successful, in line with extremist tendencies which characterize the current European environment. Specifically, a distinction between the available options must be made, which basically are: a joint international operation – under the auspices of the United Nations and the EU; an Italian intervention, even without other “willing” partners; the non-intervention option, or one of economic nature.

As far as the first option concerns, a boots-on-the-ground operation requires an international ratification made by the international organizations. As the massive flow of irregular migrants from Libyan coasts represents a worrying concern mostly for Italy, due to its geographic position – even if redistribution quotas across Member states made them uneasy – a coalition seems not possible at the moment. Conversely, doing nothing – as well as resorting to sanctions – is not going to solve the migration issue for sure, nor the Libya’s domestic situation: risk of other tragedies, overcrowded refugee centres, complaints about EU’s inefficiency…

In case of no coalition formation, Italian intervention is not recommended. Apparently, a desire of revenge against Italy is still present, and the Islamic State’s caliph al-Baghdadi threat, according to which jihadists have reached the “south of Rome”, sounds like an attempt of attracting them and taking revenge once and for all. Not just for its colonial past, but rather for the many episodes of violence against native ethnic groups in the once called “Fourth Shore”, which are the deepest memories of Libyans about that period: the capture and killing of Omar al-Mukhtar, the hero of Libya’s resistance, is the most emblematic event which embodies such aversion.

However, any military intervention would be impossible without a plan for domestic stability promotion: the risk is to get bogged down in an Iraq 2.0 version. Proposal have been announced to close the tap of funding for Islamic extremist groups by destroying the boats used for human smuggling; still, the Tripoli government has opposed to any foreign intervention in territorial waters that would violate the principle of national sovereignty – as if there were any. In the meantime, there are some news about a letter delivered to the UN headquarters from the Tobruk government, in which it admits its incapacity of dealing with the migration and calls for cooperation with the EU. Although this would represent a leap forward for the crisis resolution, several legal and humanitarian issues remain to be dealt with, according to diplomatic sources from the Security Council.

The operation against human smugglers EUNAFOR MED is awaiting backing from the Security Council, where the High Representative has one month to negotiate an agreement with veto power countries, as the next meeting of Foreign and Defence Ministers is scheduled on 25th June. Notwithstanding its apparent success, many are the interposed obstacles, particularly the Russian refusal to any military option, or the lack of cooperation from Libyan authorities. Above all else, critiques from EU members over distribution quotas suggest that no progress has been made.

A recent article written by 300 academics for OpenDemocracy defines the European military operation as “self-serving”, explaining that this means “simply to continue a long tradition in which states, including slave states of the eighteenth and nineteenth century, use violence to prevent certain groups of human beings from moving freely”. How to destroy smugglers’ boats is another controversial point, considering that most of them are fishing vessels located in civil ports; “passengers” are embarked offshore, reaching the boat by means of dinghies: in this way, the window of time to avoid the sailing is very limited.

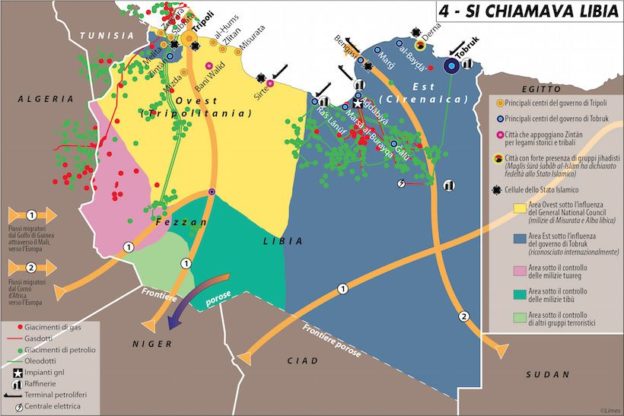

Evidently, the only admitted and effective action is one of political nature: Notwithstanding the undoubtedly remarkable work of Bernardino León, the UN Special Representative and Head of the UNSMIL Mission, and the European border assistance mission named EUBAM, the most desirable thing in the Libyan chaos would be promoting negotiations between the two main factions: the internationally recognised government based in Tobruk – judged “unconstitutional” by the Supreme Court – and the Islamist one in Tripoli, formed during the transitional phase following the Gaddafi’s downfall in 2011. The current international stance favouring Tobruk should be avoided, as doing so appeasement and the eventual state- and nation-building would be impeded. In fact, there is no absolute certainty about Daesh presence within Tripoli authorities – some argue about “franchises” of Islamic State to get a greater global impact – even if the very least possibility of such a presence make the recognition of Tobruk the most convenient choice.

A distinction between Islamists should be made. The presence of religious elements is not a threat in itself, maybe even recommended in the MENA region; as history teaches us, the isolation of a social group could lead to disastrous consequences for state stability. Extremism is what must be eradicated; although this seems to be taken for granted, sometimes it appears to be an old and too much tolerant concept in the current situation. That is why dialogue must be promoted between the two factions; failure to do so will result in the complete annihilation of a country, where the exercise of law will be prerogative of the many local tribes facing themselves in a struggle for power in which nobody is going to win. The issue to be faced is not migration, but the whole region’s instability.

Alessio Concettoni